Introduction

A neonatal stroke is a stroke that occurs in a baby before or around the time of birth. Some babies show symptoms right away, such as seizures, and get brain imaging that quickly leads to a diagnosis. Other babies, however, may not show symptoms until later. For example, as they grow up, they might have delays in speech development (e.g., late first words) or motor development (e.g., one side of the body is weaker, difficulties with balance and coordination) as compared to same-aged peers. In these cases, the stroke might not be diagnosed until months or even years after it happened.

For parents, hearing the news that their child had a neonatal stroke can be overwhelming, confusing, and distressing. Many parents worry about how the stroke will affect their child’s development. It is important and helpful for parents to understand how neonatal stroke can impact neurocognitive development. Neurocognitive outcomes are the long-term effects of neonatal stroke on the brain’s development. Neurocognitive development involves thinking skills (e.g., language, attention, learning), which also affect social-emotional functioning and behaviors (e.g., processing and managing feelings, interacting and communicating with others, self-regulating behaviors).

In this article, we focus on the most common neurocognitive challenges associated with neonatal stroke. However, parents should know that each child is unique and there are many reasons for differences in outcomes among children with neonatal stroke. One important reason is that a stroke does not affect the brain in the same way in every child. The location and size of the stroke in the brain will impact which brain functions and connections are damaged and how severe the damage is. As such, two children with neonatal stroke may have different outcomes. Another reason for these differences is that each child has their own set of genes and environment to grow up in. This means that even the exact same stroke may impact two children differently.

Neurocognitive outcomes: attention and executive functions

Neonatal stroke has been associated with a wide range of possible neurocognitive impairments, and there is significant variability across children. Overall intellectual development is generally within the average range, leaning towards the lower end of average. In other words, intelligence can be normal or mildly affected, but severe deficits are uncommon. Cognitive domains commonly affected include attention and executive functions (EFs). EFs are mental skills that help us focus, resist distractions, multi-task, plan and organize, make decisions, and control our actions. They are like the CEO of our brain, helping us use our thinking skills effectively.

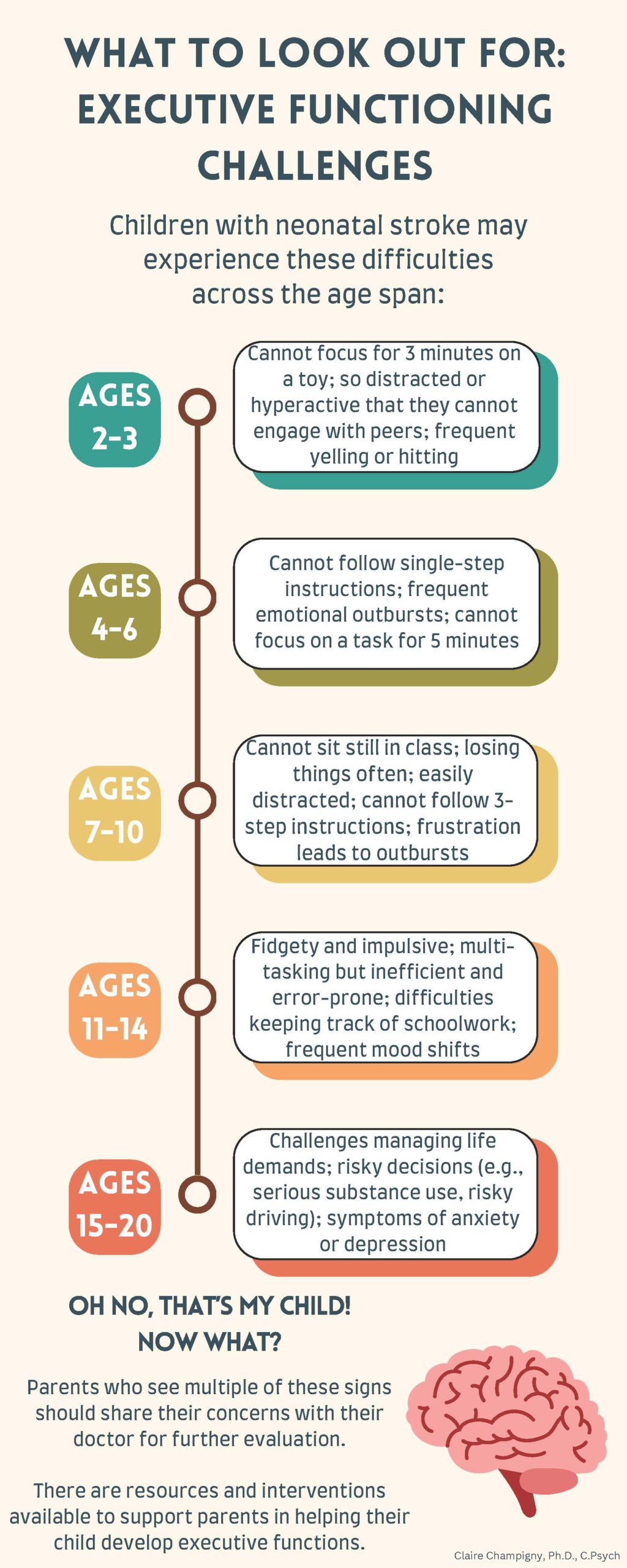

The development of EFs is dynamic and complex. The basic foundations of EFs begin developing in infancy, such as when a baby focuses their attention on a parent’s face. EFs develop more in early childhood; picture the difference between a 2-year-old who immediately cries when not given something and a 4-year-old who is learning to control their impulses and follow simple instructions. As children get older, they get better at planning and organizing, can follow more complex instructions, can pay attention for longer, and begin to use more self-control (e.g., waiting their turn for a game, raising their hand to speak in class). Around age ten, more advanced EF skills develop, like problem-solving, task-switching, and planning and organization (e.g., managing a large school project, figuring out steps to solve problems). In adolescence, EF skills are used to plan for the future, consider consequences, and juggle demands (e.g., schoolwork, social life). EFs continue to mature until early adulthood, in our 20s, when the brain refines skills like impulse control, long-term planning, and self-regulation.

How does this information about EF development relate to neonatal stroke? This is particularly important for strokes that happen early in life because it may be several years before EF challenges appear. They may show up years after the stroke because EF skills take time to mature.

What neurocognitive difficulties should parents look out for?

By toddlerhood, some children with stroke may show attention and impulsivity difficulties as they get older. A toddler with a history of stroke is more likely to have difficulty sustaining their attention even on brief, engaging activities, compared to other children their age. They may also have more difficulty controlling their behavior and inhibiting impulsive responses, which could then look like yelling or hitting, for example. However, many children with neonatal stroke do not show signs of impairment at this early age. Instead, it is common for EF deficits to become noticeable during school age. Once children start school, newer demands are placed on them, which can make these difficulties more apparent, both in the classroom and at home. The child may be particularly distracted in a busy classroom, lose track of instructions, frequently lose their homework, forget their jacket, and not know what homework is due. Additionally, difficulties with inhibition and impulse control can occur, which may look like speaking out of turn.

EFs are also relevant when looking at the development of a child from a social-emotional and behavioral perspective. Because EFs help us control our behavior and thinking, they are involved in how we respond to events and emotions too. EFs play a key role in self-regulation. A toddler, from 1-2 years old, who has experienced a neonatal stroke may face greater challenges with self-regulation than their peers of the same age. In terms of behavior regulation, parents may notice that their toddler is more likely to yell or hit impulsively, or show hyperactive behaviors (e.g., restless, fidgety). As the child grows up, difficulties with behavior regulation may affect their schooling (e.g., not staying seated in class) and relationships with peers (e.g., interrupting their friends, getting into fights). In terms of emotion regulation, toddlers and children may have frequent crying, mood shifts, or outbursts.

What can parents do if they notice neurocognitive difficulties in their children?

The first step is noticing your child’s challenges. You are not alone – many of the difficulties described here can be noticed by parents as well as early childhood educators and teachers, who would likely communicate these concerns to you. The infographic in this article gives examples of behaviors to notice. If you see several of these, it is possible that your child has difficulties with their EFs.

There are many ways to help your child’s development. One of them is parent support or coaching. This gives parents concrete strategies to help a child’s development. Strategies may include (1) modeling behavior: children learn by watching their parents plan tasks, solve problems, regulate behaviors, and manage emotions. (2) Setting routines: having regular daily routines help children develop time management skills, understand expectations, and increase independence. (3) Giving opportunities to practice EF skills. For example, help your child make age-appropriate choices, decide how to organize their room, or set goals for homework. (4) Encouraging self-regulation: parents can teach their child ways to manage strong emotions and calm down when they are upset. Techniques like deep breathing or taking a break from the situation can be helpful. (5) Giving specific praise: when children try to use their EFs, parents can praise their efforts. This helps build confidence. Specific praise is especially helpful because it tells children exactly what they did well and encourages them to repeat that behavior in the future. For example, while saying “good job” is vague, saying “I love how you are playing so gently and calmly” is encouraging gentle behaviors. (6) Helping with problem-solving: parents can guide their children in thinking through problems by helping them consider different solutions and their pros and cons. This builds decision-making and planning skills. These strategies are helpful for all children to develop their EF skills.

If you are concerned about your child’s development – this can include the difficulties described in the article and infographic, as well as any other ones, such as delays in, challenges with literacy, or slow learning – speak with your family doctor. Your doctor will ask questions to better understand the issue and, if necessary, provide appropriate referrals for further evaluation (e.g. to a neuropsychologist or developmental pediatrician) and intervention.

About the Author

Claire Champigny

Dr. Champigny is happy to answer questions and receive feedback about her article. Please contact her via email at claire.champigny@sickkids.ca.

Graphics: Claire Champigny, PhD

Medical Editor: Jenny Wilson. MD, MS

Junior Editor: Jeehyun Kim