What is rehabilitation?

What is rehabilitation?

After a stroke, the brain works on healing itself by making new connections between neurons around the injury. These new pathways within the brain help the child continue to learn and grow. This process is called neuroplasticity, which means the brain can change. Rehabilitation uses neuroplasticity to help patients regain lost skills. It also teaches patients to adapt to their difficulties, use their strengths, and find new ways to do everyday tasks. The goal of rehabilitation is to help kids recover as much function as possible, build new skills, and do things on their own.

When does rehabilitation start and end?

Rehabilitation can start immediately after a child is safe and stable after a stroke. The medical team will check the child’s skills and needs, then set up the right services. Early support matters because children often make the most progress in the first 6 to 12 months after a stroke. Some children continue rehabilitation for many years.

Rehabilitation often starts in the hospital and continues at home or in outpatient clinics. It can change over time because children with stroke may have trouble learning new skills, not just losing skills they already had. Some problems from a stroke may not be seen until years later as the child grows. For instance, babies who have had a stroke might seem fine at first, but over time, tests may reveal difficulties in thinking, language, or motor skills. cognitive, language, or motor skills.

Children and adolescents’ brains are still growing at the time of the injury, they need long-term follow-up to track progress. Regular visits help the healthcare team adjust rehabilitation services as the child’s needs change.

What does rehabilitation look like?

Depending on where the stroke occurred in the brain, each child will experience different challenges. They may have difficulty thinking, speaking, reading, walking, or using their hands. Every child’s stroke is different, so their recovery plan will be unique.

Depending on where the stroke occurred in the brain, each child will experience different challenges. They may have difficulty thinking, speaking, reading, walking, or using their hands. Every child’s stroke is different, so their recovery plan will be unique.

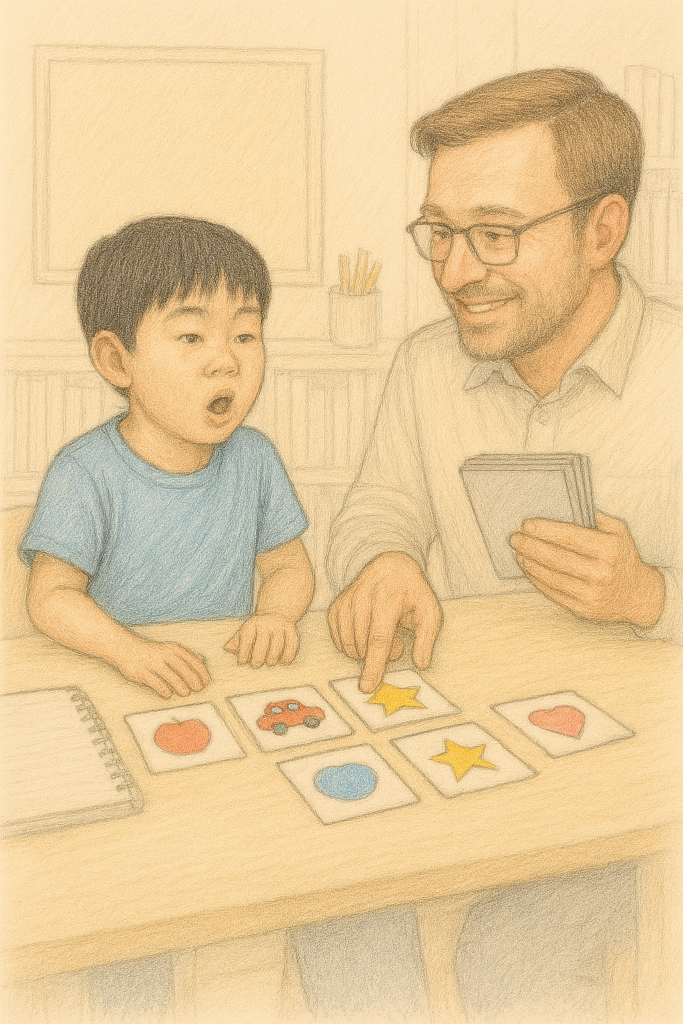

The most common specialists seen after pediatric stroke include:

- Physical therapists: They help improve strength, balance, and movement. For example, they work on walking, preventing falls, climbing stairs, and building muscle strength.

- Occupational therapists: They help children learn daily skills and hand use. They help with things like getting dressed, eating, and writing. They also use special tools when needed, such as hand splints, pencil grips, and special eating utensils.

- Speech-language pathologists: They support communication, speech, and feeding. They may help with things like language, articulation, and swallowing food.

- Neuropsychologists: They guide cognitive (thinking) skills and learning. They may help with things like study strategies, emotional and behavioural support, and school support for learning challenges.

The specialists a child might see after a stroke can vary depending on the country, geographical region, and even the organization providing care. Titles and roles may differ, but what matters most is that the specialist has the right training to meet the child’s needs. Families can ask their medical team questions to ensure that their specialist is qualified.

The role of family

Parents and caregivers play an important role in rehabilitation. They can encourage therapy goals at home, help children practice exercises, support them emotionally, and help with learning to use special equipment. Progress can be slow, and many stroke patients feel frustrated, sad, angry, and hopeless at times. Patience, love, and support from their family help many patients keep working toward their goals.

Conclusion

With a good rehabilitation team and a supportive family, many children can regain skills and adapt to life after a stroke. New research in rehabilitation is also opening new doors for recovery. If your child has had a stroke, ask your healthcare team about rehabilitation options and community resources.

About the Author

Dr. Claire Champigny, Ph.D., C.Psych

Dr. Claire Champigny is a postdoctoral fellow in clinical pediatric neuropsychology at the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Canada). She conducts neuropsychological assessment for children with a range of medical histories across clinics (e.g., Neurology, Neurosurgery, Oncology), and also works as a therapist providing support for parents of children with behavioural challenges and complex medical needs. Dr. Champigny’s research interests primarily revolve around neurocognitive and mental health outcomes following pediatric stroke.

Dr. Champigny is happy to answer questions and receive feedback about her article. Please contact her via email at claire.champigny@sickkids.ca.

Graphics: Claire Champigny, Ph. D., C. Psych.

Medical Editors: Ilona Kopyta

Junior Editor: Gia Singh