Imagine your body as a playground, and your red blood cells as little adventurers rolling down a hill. Normally, they’re like smooth stones, rolling along without a hitch. But, for someone with sickle cell disease, it’s like sending a box down that hill—not so smooth. Instead of being round and bouncy, their red blood cells become crescent-shaped and deflated, making it tough for them to journey through blood vessels. This unique shape can cause health problems, and that’s why doctors and researchers dive into the world of clinical trials. These trials are like exciting investigations where they try to find better ways to help those with sickle cell disease, making their journey a bit smoother.

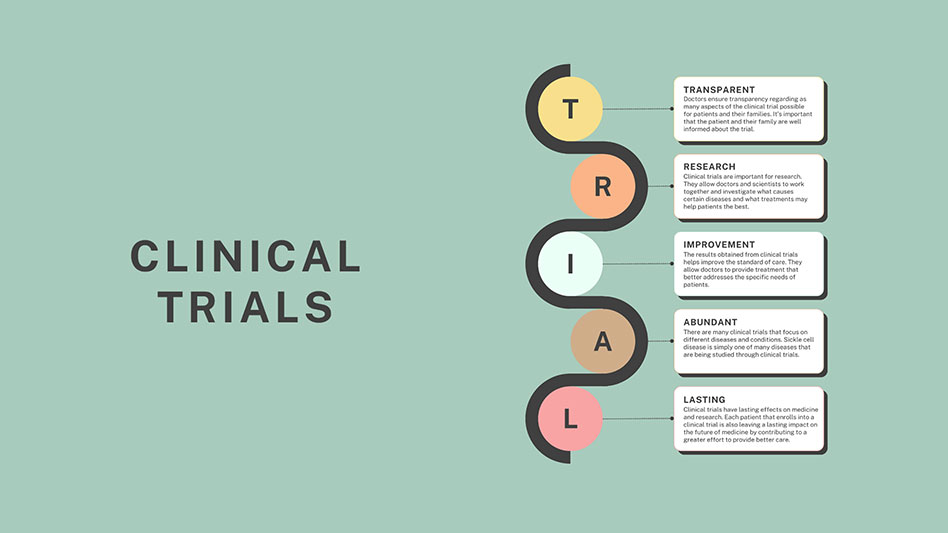

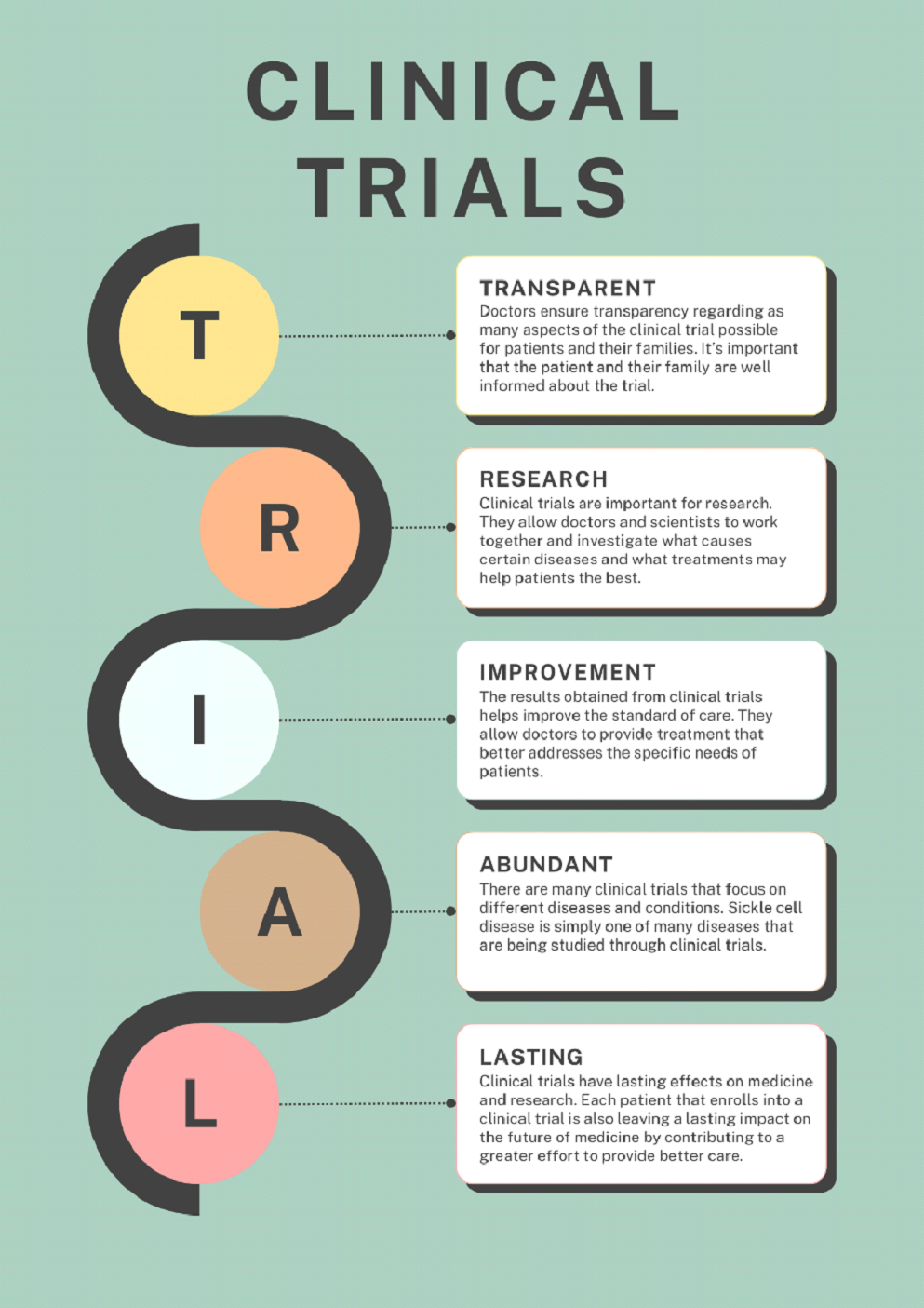

Clinical trials are like detectives solving mysteries about diseases, especially tricky ones like sickle cell disease. They’re a good way to find answers to important questions and figure out how to treat diseases. It’s like a race. For a while, our understanding of diseases was moving faster than our ability to make effective treatments. But clinical trials help us catch up. They teach us how to treat patients with sickle cell disease better and make sure fewer people have to struggle with it in the future. When doctors invite parents and patients to join clinical trials, they want everyone to understand what’s going on, so they share all the information they can. It’s important to know that doctors often can’t select which treatment someone gets in a trial. Joining the trial is completely up to the parents and patients, and even if they decide not to, doctors will still provide them with the best care.

Clinical trials play a crucial role in the sickle cell disease community. Although sickle cell disease was the first inherited disease closely studied by scientists, they didn’t focus much on treatments for a while. In recent decades, more clinical trials have been carried out, and the results have led to changes in the standard of care.

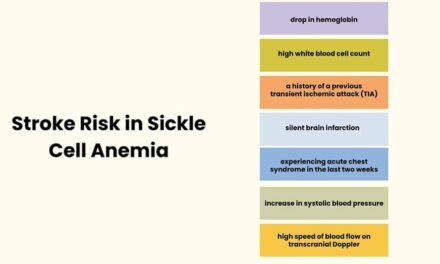

An important trial from the late twentieth century, called STOP, examined kids with sickle cell disease to understand their risk of having a stroke. High-risk children were split into two groups. One group received blood transfusions only as needed, which was standard of care at the time. The other group received blood transfusions on a regular basis. It turns out that regular blood transfusions were more effective in preventing strokes. This trial transformed how doctors care for sickle cell patients. Then came STOP II, which showed that stopping transfusions for children who always got them wasn’t safe. This new information helped doctors plan better treatments. In a related trial called TWiTCH, they found that a medicine called hydroxyurea may be as effective as regular blood transfusions for reducing stroke risk in children with sickle cell disease. Thanks to these trials, the standard of care has changed and doctors now have improved ways to care for patients with sickle cell disease.

Today, scientists are looking into new types of medicine that seem promising for treating sickle cell disease. But to make these new treatments, they need the help of people with sickle cell disease. Scientists work closely with doctors, who know what treatments might work best for their patients. It’s like having a teammate who understands the game plan. The family also plays a big role. They need to be motivated and stick to the plan, like teammates cheering each other on.

Looking at the bigger picture, these trials are like puzzle pieces. Each trial gives us a piece of the puzzle, and when we put them all together, we can create new and better treatments for sickle cell disease.

About the Author

Christine Zhang

Pre-medical Student

Christine Zhang is a dedicated second-year student at UCLA, where she is actively pursuing a Bachelor of Science degree in Physiological Sciences. Her academic journey is driven by a passion for understanding the intricacies of the human body. Looking beyond her undergraduate studies, Christine aspires to attend medical school after graduation, aiming to make a positive impact in the realm of healthcare.

Her specific interest lies in the field of pediatrics, where she envisions herself contributing to the well-being of young patients. Christine is enthusiastic about exploring the intersection of research and healthcare, recognizing the importance of bridging these realms to advance medical knowledge and improve patient outcomes.

Email: czhang706@g.ucla.edu

Junior Editor: Isabella Estrada