Author: Rania I. H. Ismail, MB.Bch, MSC, MD, IBCLC

Perinatal stroke is a stroke in a baby that occurs between 28 weeks of pregnancy and 28 days after birth.

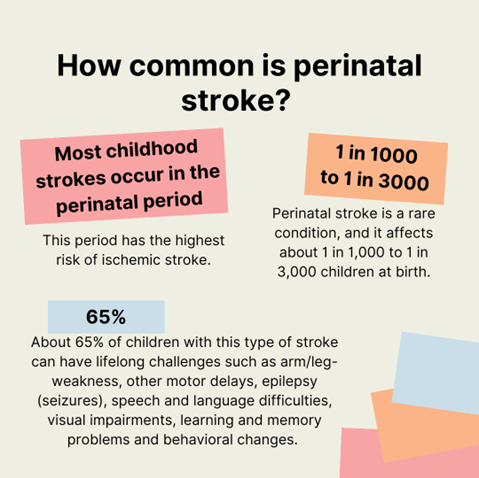

How common is perinatal stroke?

Most childhood strokes occur in the perinatal period. This period has the highest risk of ischemic stroke. Ischemic stroke is the most common type of stroke (there are two main categories of stroke) and it occurs when a blood vessel to the brain is blocked.

Perinatal stroke is a rare condition, and it affects about 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 3,000 children at birth. However, about 65% of children with this type of stroke can have lifelong challenges such as arm/leg-weakness, other motor delays, epilepsy (seizures), speech and language difficulties, visual impairments, learning and memory problems and behavioral changes. This can cause significant economic and social burden in caring for a child with stroke throughout their lifespan.

Early diagnosis and risk factor recognition:

It’s not easy to identify perinatal stroke before birth or in newborns.

Stroke can present as subtle signs in babies. They might have apnoea, where they stop breathing for a short time. They might also have feeding problems. A baby might be more drowsy than normal. They also can have abnormal movements, called seizures, often affecting one side of the body.

In the Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries the ‘Butterfly Effect’ is defined as the idea that a very small change in one part of a system can have large effects in other parts. Similarly, perinatal stroke is sometimes only recognised later in life when problems arise with a child’s movement or learning. As a child’s brain evolves over many years, any problem they might have can only be noticed around the age where those abilities are meant to develop. For example, grasping objects starts approximately at the age of 3-4 months. This is why most “presumed perinatal ischemic stroke” (PPIS) cases are diagnosed at this age when an infant consistently uses only one hand to grasp objects and ignores the other hand or keeps it fisting. Complex learning hardships may not be recognized for a long time till a child enters school.

It is a big dilemma to reach a definite cause for a case of perinatal stroke.

In most of these stroke cases, the cause is not known for sure. It’s possible a blood clot in the placenta got dislodged, passed through a natural hole in the fetal heart and then blocked brain arteries (blood vessels) causing a stroke.

Established risk factors for stroke in babies such as severe congenital heart disease and infections like bacterial meningitis are easy to diagnose. However, these risk factors are found only in a small number of cases. Other risk factors like blood clotting disorders may have a role in some cases, mostly those cases with family history. Placental disorders like infection of placenta and other causes of placental blood clots are hard to identify. Research to date has not found a strong relationship between common conditions of pregnancy and perinatal stroke.

It is particularly important for mothers to understand that there is usually nothing they did or did not do during their pregnancy that caused their child’s stroke.

Since we don’t understand the causes of most perinatal strokes, it is not possible to identify mothers or children at risk. As a result, there are no preventive measures that could have been taken.

Management plan:

A baby who has experienced a stroke may need neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission and close monitoring for poor feeding or seizures.

Tests needed to understand each case will depend on the child’s individual circumstance. Some common tests are:

- A brain scan like US, CT or MRI may confirm a stroke and find out if it’s due to a clot or a bleed. Such imaging could diagnose Neonatal Arterial Ischemic Stroke (NAIS), Neonatal Cerebral Sinovenous Thrombosis (CSVT) or Neonatal Hemorrhagic Stroke (HS). Brain MRI is the test of choice to detect infarcts (the brain injury seen in an ischemic stroke).

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) is often done for concern of seizures that may be a complication of the stroke

- Testing for blood clotting disorders is often done for babies with family history or recurrent clotting events.

- Screening for heart problems.

Recurrence risk:

The risk of stroke for parent’s future pregnancies is very low. Current evidence also suggests that the risk of another stroke in childhood in an otherwise healthy child with a perinatal stroke is likely <1%. In other words, nearly 99% of children with a perinatal stroke will not have another childhood stroke. There has not been any major linkage between genetics and perinatal stroke. Children with complex congenital heart disease may be at risk for additional strokes, and their doctors will consider treating with medications, like blood thinners, to prevent strokes (see the other article in this issue about stroke in congenital heart disease for more information). Fortunately, the overall risk in most cases will stay low.

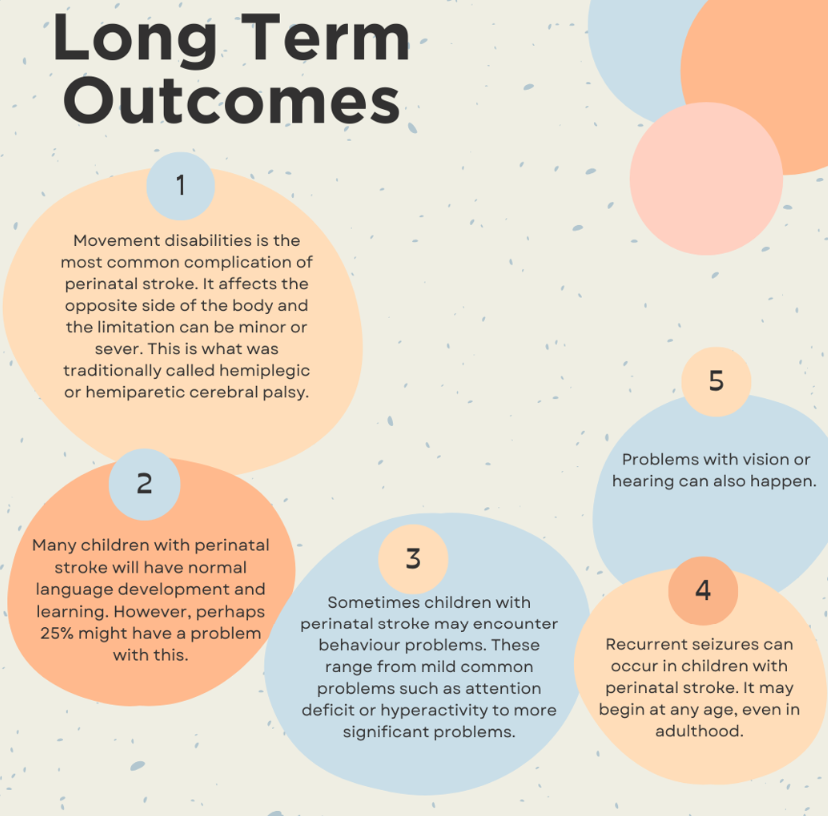

Long term outcomes:

Long term outcomes:

1. Movement disabilities is the most common complication of perinatal stroke. It affects the opposite side of the body and the limitation can be minor or severe. This is what was traditionally called hemiplegic or hemiparetic cerebral palsy.

2. Many children with perinatal stroke will have normal language development and learning. However, perhaps 25% might have a problem with this.

3. Sometimes children with perinatal stroke may encounter behaviour problems. These range from mild common problems such as attention deficit or hyperactivity to more significant problems.

4. Recurrent seizures can occur in children with perinatal stroke. It may begin at any age, even in adulthood.

5. Problems with vision or hearing can also happen.

Treatment:

Risk factors detection and early diagnosis is not always feasible. Treatments are designed around each specific challenge that may arise. Treatment plans must be tailored to each child. This can include different types of therapy, assistive devices, treatment of seizures and surgery if needed.

New treatments are emerging. Some examples are Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT), non-invasive brain Stimulation by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) or Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (TDCS). TDCS is being studied in adult stroke and is just starting to be applied to children with perinatal stroke.

Different therapy methods are being evaluated for stroke, such as stem cell therapy. There is no available evidence to evaluate the benefits and harms of stem cell-based treatment. Stem cell therapy could help treat symptoms of stroke in the future, but it still needs more time to advance.

References:

- Roy B, Webb A, Walker K, Morgan C, Badawi N, Nunez C, Eslick G, Kent AL, Hunt RW, Mackay MT, Novak I. Prevalence & Risk Factors for Perinatal Stroke: A Population-Based Study. Child Neurol Open. 2023 Dec 17;10:2329048X231217691. doi: 10.1177/2329048X231217691. PMID: 38116020; PMCID: PMC10729630.

- Rajapakse T, Kirton A. NON-INVASIVE BRAIN STIMULATION IN CHILDREN: APPLICATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS. Transl Neurosci. 2013 Jun;4(2):10.2478/s13380-013-0116-3. doi: 10.2478/s13380-013-0116-3. PMID: 24163755; PMCID: PMC3807696.

- Gillick B, Menk J, Mueller B, Meekins G, Krach LE, Feyma T, Rudser K. Synergistic effect of combined transcranial direct current stimulation/constraint-induced movement therapy in children and young adults with hemiparesis: study protocol. BMC Pediatr. 2015 Nov 12;15:178. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0498-1. PMID: 26558386; PMCID: PMC4642615.

- Bruschettini M, Badura A, Romantsik O. Stem cell-based interventions for the treatment of stroke in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Nov 23;11(11):CD015582. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD015582.pub2. PMID: 37994736; PMCID: PMC10666199.

Key words: Perinatal stroke, seizures

About the Author

Dr. Rania I. H. Ismail

MB.Bch, MSC, MD, IBCLC Professor of Pediatrics & Neonatology

Dr. Rania I. H. Ismail is also member of Basma M Shehata’s Lab in the Department of Pediatrics at Ain Shams University

Medical Editors: Gayatra Mainali, MD

Junior Editor: Ingrid Votruba and Karen Glenn