What is a stroke?

A stroke occurs when a blood vessel (artery) carrying blood with oxygen and nutrients to the brain is blocked (ischemic stroke). It can also occur when that blood vessel bursts and bleeds (hemorrhagic stroke). Sometimes a vein which drains blood away from brain can also get blocked. This can cause venous stroke (medically known as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis). Damage to the brain tissue causes symptoms like weakness on one side of the body or difficulty talking. In newborns and young children, stroke can also present as a seizure.

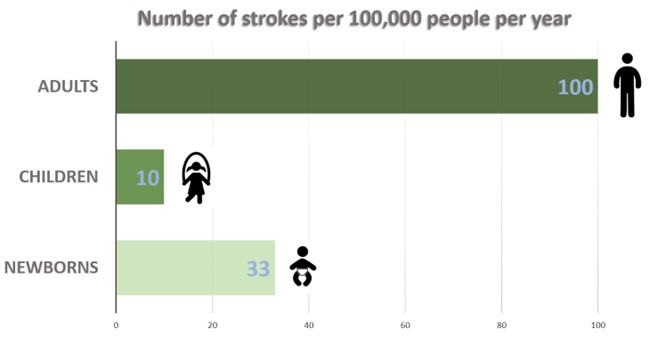

Strokes do not just happen in adults

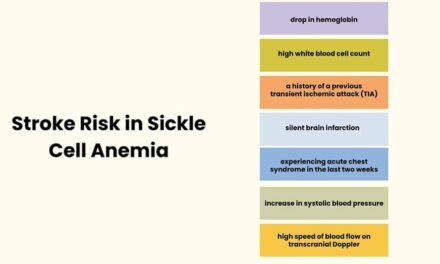

While less common than in adults, stroke is an important cause of brain injury in children. In developed countries like the United States, about 7,000 children have a stroke every year. Boys and children less than 5 years old are at higher risk. Newborns are at particularly high risk. One out of every 3000 newborns have a stroke. Children with heart problems, sickle cell disease, and abnormalities with clotting, have a high risk of strokes.

Neonates (newborns) with stroke

When a baby has an arterial ischemic stroke, the first symptom is usually a seizure. However, sometimes a baby with stroke will not have any symptoms. Months later that child may start having seizures or may develop weakness in their hand or leg. This weakness is called cerebral palsy. The old stroke is then discovered on a brain scan like an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). For these babies, doctors provide supportive care, treat seizures or infections, and ensure good hydration and electrolyte balance. The seizures usually stop after a few days and it becomes safe to stop anti-seizure medications before the baby goes home. The risk of a baby having another stroke is very low, around 1%, so most babies do not need aspirin or blood thinners to prevent future strokes. Some babies may have a medical condition, like a heart defect, which puts them at risk for more strokes. These babies may need to take aspirin or blood thinners. There are researchers studying other ways of treating babies with stroke. One such way is using stem cells. However, more research is needed to determine if this is safe and helpful for babies with stroke.

In addition to arterial ischemic stroke, babies can have other types of strokes. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is sometimes treated with anticoagulation (blood thinners), which some research shows helps with recovery. Treatment of hemorrhagic stroke is with supportive care. Only in rare cases is a brain surgery is needed to remove the blood.

We often do not know why a baby has a stroke. With ischemic stroke, it may be that a clot from the placenta travels to the baby, passing through the heart and going to the brain; However, this is difficult to prove. While it is natural for a parent to feel guilty or to look for reasons why their baby had a stroke, it is important to know that it is generally not anybody’s fault. It is not because the baby’s parents did something wrong during pregnancy or delivery.

Older children with stroke

When most children have a stroke, they will suddenly have the following symptoms: weakness on one side of their face and body, difficulty talking, difficulty seeing, or balance problems. Children may also have headaches, sleepiness, or seizures. There are often delays in recognizing that a child has a stroke because physicians don’t expect it to occur in a child. It can also take time to get the imaging test (MRI) that proves a stroke has occurred.

Treatment of stroke of arterial ischemic stroke

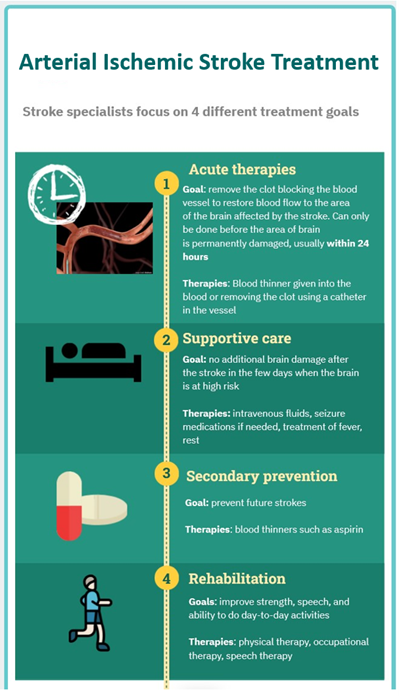

Much has changed in treating strokes in children over the last decade. In general, treatment for strokes focus on four different things: 1) acute therapies which open a blocked blood vessel to restore blood flow to undamaged parts of the brain (thrombolysis or thrombectomy), preventing any further brain damage in the days after, 2) supportive care, 3) preventing future strokes, and 4) rehabilitation for children who are weak or have new difficulties because of the stroke.

Acute therapies for arterial ischemic stroke

Acute therapies can prevent permanent brain damage if the treatment is given in time, usually within 24 hours or less. Thrombolysis is a treatment where a strong blood thinner (for example, tissue plasminogen activator or Tenecteplase) is given into the blood to dissolve the clot in the brain. One of the most exciting advances in stroke care is thrombectomy. With this treatment, the clot is removed from the vessel in the brain using a catheter. The catheter is placed in a blood vessel in the leg. For some adults with stroke this treatment can be dramatically helpful. Based on what we know about clotting in children, we would expect these therapies to work. However, since stroke is much less common in children and is difficult to diagnose quickly, we don’t have the research studies to prove these therapies are helpful for children. We do not know the best dose of thrombolytics for children. Despite this, children are sometimes treated with thrombolysis or thrombectomy under the care of pediatric stroke experts who follow consensus -based guidelines and have developed workflows at their hospitals prepared specifically for these situations.

While there may only be 1-2 children per year treated with acute therapies at one hospital, researchers collect information from these children to learn about the safety and effectiveness of the therapies. The largest study, SaveChilds trial, suggests that thrombectomy can be safe even in small children if it is done by a neuro-interventional radiologist with experience treating children.

Supportive care

After a stroke, children are monitored in the intensive care unit. To prevent any further brain injury, they are given supportive care. This care includes: maintaining normal to slightly high blood pressure, normal temperature and blood sugars, and being positioned flat (in most cases) to maximize blood flow to the brain.

Secondary prevention of arterial ischemic stroke

Most children are given aspirin as a daily medication to prevent any more strokes from happening. Sometimes a stronger blood thinner (anticoagulation) is used if the child has a condition that makes it more likely for them to have another stroke. This can involve an abnormality of the heart or blood vessels. The decision of which medication to use is carefully considered for each child. Physicians account for the specific aspects of their stroke and balance the risks of bleeding and clotting.

Special conditions that cause arterial ischemic stroke

Some rare disorders put children at high risk for having a recurrent stroke. One of these is called moyamoya disease. In moyamoya disease, the blood vessels that provide blood to the brain become increasingly narrowed, depriving the brain of the blood it needs. As this is happening, children may have headaches, brief episodes of neurologic symptoms called transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), seizures and strokes. Aspirin may be helpful in preventing strokes; however, the best treatment is a surgery which provides new blood vessels to the brain (“revascularization”).

Outcomes

Children’s brains have impressive capacity to heal and “rewire” after a stroke. However, a stroke often causes permanent problems for children. Newborns who have a large stroke often develop a motor disability affecting one side of the body called hemiplegic cerebral palsy. They are also at high risk of having epilepsy and learning difficulties. Despite this, most of these children will walk, participate in activities, and lead full lives. Older children with stroke may also have more difficulties in school, with speech, and may have difficulties with their motor skills.

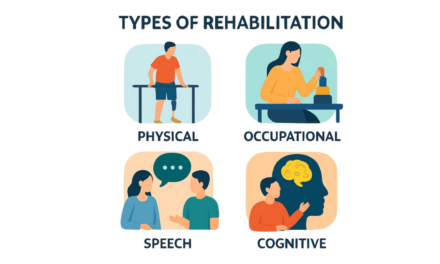

Rehabilitation therapies can be very helpful in recovery and support of children with stroke. There are new and exciting therapies being studied. For example, constraint-induced movement therapy is an approach that can be very helpful for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. It encourages children to use the side of their body affected by the stroke. Another treatment that is being studied is noninvasive neuromodulation used along with regular physical or occupational therapy. This involves the placement of either electrical or magnetic currents on the outside of the head to activate certain areas of the brain. This may “prime” the brain to get more benefit from the physical therapies the child is doing.

Resources

- World Stroke Organization Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022

- Sporns PB, Sträter R, Minnerup J, Wiendl H, Hanning U, Chapot R, Henkes H, Henkes E, Grams A, Dorn F, Nikoubashman O, Wiesmann M, Bier G, Weber A, Broocks G, Fiehler J, Brehm A, Psychogios M, Kaiser D, Yilmaz U, Morotti A, Marik W, Nolz R, Jensen-Kondering U, Schmitz B, Schob S, Beuing O, Götz F, Trenkler J, Turowski B, Möhlenbruch M, Wendl C, Schramm P, Musolino P, Lee S, Schlamann M, Radbruch A, Rübsamen N, Karch A, Heindel W, Wildgruber M, Kemmling A. Feasibility, Safety, and Outcome of Endovascular Recanalization in Childhood Stroke: The Save ChildS Study. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jan 1;77(1):25-34. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3403. PMID: 31609380; PMCID: PMC6802048.

- Ferriero DM, Fullerton HJ, Bernard TJ, Billinghurst L, Daniels SR, DeBaun MR, deVeber G, Ichord RN, Jordan LC, Massicotte P, Meldau J, Roach ES, Smith ER; on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Management of stroke in neonates and children: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50:e51–e96.

- Gonzalez F, Ferriero DM. Stem cells for perinatal stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2022 Jun;21(6):497-499. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00142-9. PMID: 35568038.

- Hilderley AJ, Metzler MJ, Kirton A. Noninvasive Neuromodulation to Promote Motor Skill Gains After Perinatal Stroke. 2019 Feb;50(2):233-239. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.020477. PMID: 30661493.

- Pediatric Brain Stimulation Lab

About the Author

Janette Mailo, MD, PhD, FRCPC

Pediatric Neurocritical Care

Dr. Janette Mailo is currently appointed as Assistant Clinical Professor in the Department of Pediatrics in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry at the University of Alberta. She is a long-standing member of the International Pediatric Stroke Study (IPSS) and International Pediatric Stroke Organization. She is also a member of the IPSO Editorial Board and IPSO Communications Committee.

Jenny Wilson, MD

Pediatric Neurology

Dr. Jenny Wilson is a pediatric neurologist at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon where she sees children with stroke, cerebral palsy and developmental disabilities. She is the co-chair of the Communications Committee of the International Pediatric Stroke Organization (IPSO) and serves on the IPSO Kid Stroke Connections Editorial Board.

Email: wilsjen@ohsu.edu

Graphics: Jenny Wilson, MD

Medical Editor: Gayatra Mainali, MD

Community Editor: Nirveen Kaur