The following article has been written after a conversation with Dr. Marcela Torres, a pediatric hematologist at Cook Children’s Hospital in Fort Worth, Texas. We discussed an overview of Sickle Cell Disease, its relation to Stroke, and differences in care and treatment between North and South America

Overview of Sickle Cell Disease

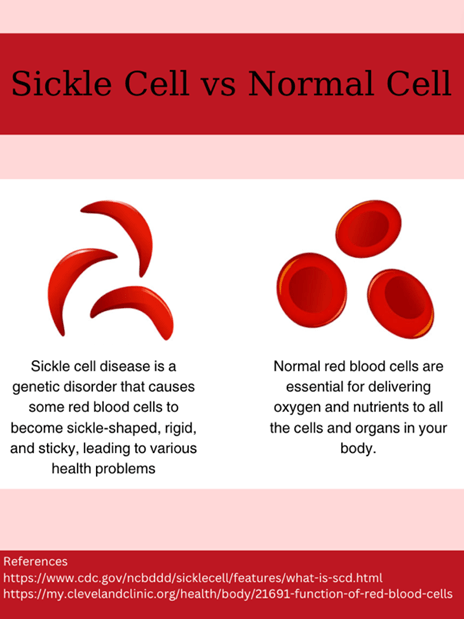

Imagine your body as a city with a network of roads and highways with bustling cars. Now, if some of those cars became misshapen or broke down, traffic jams would run rampant. This is much like what happens in Sickle Cell Disease (SCD), a genetic condition where red blood cells turn from flexible discs into ridged, sickle shapes. According to Dr. Torres, Sickle Cell Disease is the result of a mutation within a gene that tells the body how to make hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. In SCD patients, there are higher levels of hemoglobin S (Sickle hemoglobin), which cannot carry oxygen as well as normal hemoglobin. This deoxygenation (removal of oxygen from the blood) causes the red blood cells to develop the sickle shape, become much stiffer, and interact with other parts of the body much differently than normal, which can cause further problems such as stroke.

How does Sickle Cell Disease Relate to Stroke?

Stroke is a serious condition that occurs when the blood supply to part of the brain is cut off, causing less nutrients and oxygen to reach the brain. But how does Sickle Cell Disease cause a blockage in the brain? Turns out, as Dr. Torres explained, there are quite a few different ways SCD and stroke are associated. For one, the shape of the red blood cells can cause a loss of flexibility and lead to them sticking to each other. Additionally, sickle cells can stick to the endothelial, or blood vessel walls, making it easier to form blocks. Also, sometimes the affected red blood cells can burst, a case called hemolysis, which releases certain molecules and microparticles that activate an increase in platelet adhesion, forming blood clots. A combination of all these specific changes, along with many others (such as inflammation, swelling, etc.) causes a higher risk of stroke and other conditions such as Moyamoya Disease, which is a rare condition where blood vessels in the brain become narrower.

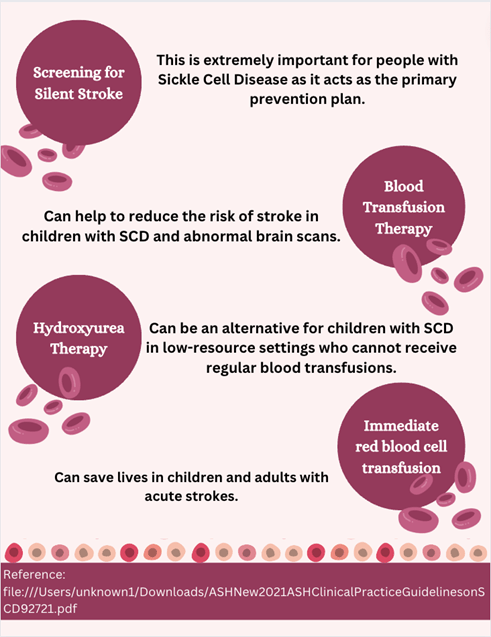

In terms of stroke, there are two main types: those that are caused by a blockage in arteries (ischemic) and those that are caused by bleeding in the brain (hemorrhagic). In terms of SCD, arterial ischemic stroke is most seen, though “silent strokes” (brain injury called infarcts without any stroke symptoms), transient ischemic attacks (TIA, which are stroke symptoms that occur quickly and then go away), and hemorrhagic stroke can occur. According to Dr. Torres, in children with SCD, the most recognized complications include arterial ischemic stroke, silent strokes, and Moyamoya Disease. In fact, according to the American Stroke Association, silent strokes occur in almost 39% of children by the age of 18 if they do not receive preventative treatments [1].

Stroke Prevention and Treatment in North America

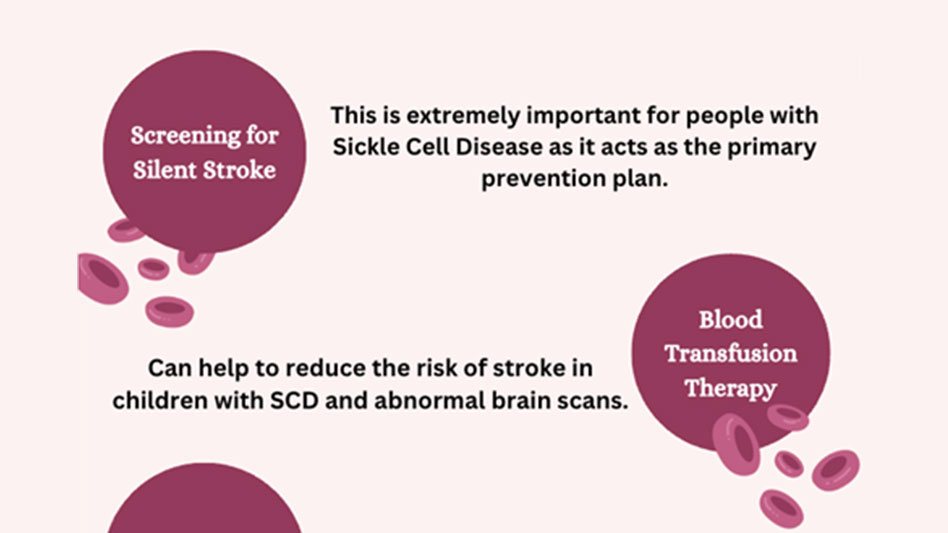

The most common primary prevention for stroke, especially in people with Sickle Cell Disease, is early screening with the use of the Transcranial Doppler (TCD), a type of ultrasound scan that looks at the velocity (speed and direction) of blood flow in the brain. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) both recommend that the TCD be done in children once every year for two years. However, as Dr. Torres stated, this is not always easy to do since the necessary tools, equipment, and trained people are sometimes unavailable; But in hospitals that have a specific program for Sickle Cell Disease, these types of tests are very common. As explained by Dr. Torres, if the scans show something abnormal, blood transfusion is recommended immediately, every 3-4 weeks for 12-18 months. Afterward, if further brain scans, such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are done and thought to be normal, other treatments can be used, such as Hydroxyurea, which is a medication that helps to prevent sickle-shaped red blood cells and is often used in chemotherapy. However, according to Dr. Torres, Hydroxyurea is often started in SCD patients even before all of this is done for other complications of the body. Another emerging treatment plan that Dr. Torres mentioned is increasing hemoglobin F (fetal hemoglobin) in people with SCD. Fetal hemoglobin binds to oxygen a lot stronger than adult hemoglobin, so this will help to balance hemoglobin S, which has increased levels in SCD patients.

Overall, in children with Sickle Cell Disease, blood transfusion and exchange transfusion are the main treatment options. But what’s the difference between the two? Blood transfusion is when blood is transferred into the body, but exchange transfusion is when a large amount of blood is removed from the patient and then replaced with new blood. According to Dr. Torres, the American Society of Hematology states that if a patient has symptoms of Sickle Cell Disease for less than 72 hours, transfusion should start within 2 hours [2]. Usually, a blood transfusion is done, unless the patient already has too much blood or hemoglobin which is when an exchange transfusion is preferred. Regarding treatment of stroke, if the symptoms occurred recently, TPA (tissue plasminogen activator, which decreases blood clots) is given.

Stroke Prevention and Treatment in South America

As Dr. Torres mentioned, in South America, prevention is done as early screening, much in the same way as in North America. However, with treatment, there are certain differences. For example, in South America, blood is considered a human product, so there are regulations and laws stating that you cannot buy or sell it. Therefore, hospitals cannot buy blood from blood centers, and when a patient needs blood, people must come to donate specifically for them. For SCD, it is best to transfuse blood that is the most “phenotypically matched” (in other words, has the same characteristic and blood type between both the donor and the receiver of the blood). Thorough testing to match blood is difficult to do.

Dr. Torres mentioned that there are various reasons for this difference between North and South America, or different regions in general, concerning stroke and SCD prevention and treatment. First, it’s important to remember that some diseases may be more prevalent in certain regions, which may cause other diseases to be overlooked. Additionally, there are many variants of Sickle Cell Disease, so there is a possibility that there are fewer symptomatic variants in South America. Finally, since hematology is such a diverse field, many specific experts, instruments, facilities, and programs are needed at specific hospitals that may not always be available to treat SCD

Concluding Remarks

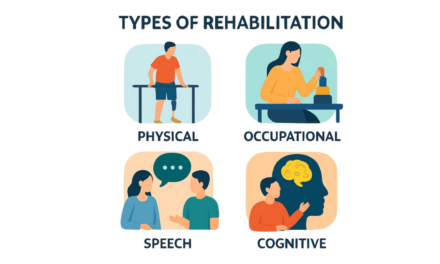

At the end of the interview, I asked Dr. Torres what the future of Sickle Cell Disease, Stroke, and healthcare in general should work to improve upon. In response, Dr. Torres stated that there needs to be unified guidelines on SCD and stroke care that large medical organizations (such as CDC or ASH) all agree upon that can become prevalent in most, if not all, hospitals. These guidelines should include what exactly needs to be done if a patient arrives with such conditions. Additionally, there should be specific programs implemented at each hospital to help give the best treatment possible. Dr. Torres also mentioned how collaboration is an extremely important aspect of support and care for people with Sickle Cell Disease, giving an example of how a patient case is often discussed with neurologists, hematologists, Sickle Cell Disease experts, and physicians in the ICU to get the most suitable treatment plan for the patient.

About the Author

Sanjana Sivakumar

Pre-Medical Student

University of California – Los Angeles Alumni

Sanjana Sivakumar is a recent graduate of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where she earned a Bachelor of Science in Neuroscience. She is a highly motivated and curious individual with a passion for exploring various topics in science and medicine. Her long-term goal is to pursue a career in medicine, specifically in family medicine and pediatrics. In her free time, Sanjana enjoys photography, reading, and playing the violin.

Medical Editors: Fiza Laheji, MD

Community Editor: Sophia Schiro