Authors: Rushel Chowhan, MBBS, and Gayatra Mainali, MD

Introduction:

Stroke at any age is a significant concern with congenital heart disease (CHD). Approximately 30% of all childhood arterial ischemic strokes are due to thrombus (blood clots) arising from the heart, usually due to congenital heart defects (present from birth), complications from medical procedures, or acquired heart diseases. Another important concern is recurrent strokes in CHD despite being on medications to prevent blood clots. Recurrent strokes are when a person who has had a stroke in the past gets additional strokes.

In this article, we discuss common types of CHD, their symptoms, how they are detected, how they can cause stroke, and what we can do to prevent recurrent strokes in children with CHD.

What is Congenital Heart Disease (CHD)?

Congenital heart disease is a defect in the structure of the heart or the heart’s great vessels that is present at birth. These defects can result in impaired blood flow from the heart, and/or reduced oxygen delivery to the body. Some common symptoms include bluish discoloration of the skin, rapid or irregular heart rate, breathing difficulty, fatigue, and poor growth or weight gain in infants.

There are two main categories of CHD. The first type—cyanotic CHD—has a higher risk of stroke.

- Cyanotic (low oxygen in the blood) congenital heart disease

- Acyanotic (blood oxygen level is acceptable) congenital heart disease

Cyanotic congenital heart disease: These are also called critical congenital heart disease. Babies with this condition can be ‘blue/bluish” with low blood oxygen levels and need surgery. Examples of Cyanotic CHD include

- Left heart obstructive lesions/impairment: Examples include hypoplastic left heart syndrome (when your heart is too small on the left side) and interrupted aortic arch (aorta is incomplete)

- Right heart obstructive lesions/impairment: Examples include Tetralogy of Fallot (a combination of four rare heart defects), Ebstein’s anomaly (a heart defect), pulmonary atresia (a heart defect), and tricuspid atresia (heart valves don’t develop correctly)

- Mixing lesions/impairment: One example is the transposition of the great arteries (when two main arteries/blood vessels leaving the heart are switched)

Acyanotic congenital heart disease examples include:

- Hole in your heart: Atrial septal defect and ventricular septal defect

- Persistence of communication between large blood vessels: Patent ductus arteriosus

- Problem with aorta/ pulmonary artery (blood vessels that carry blood out of the heart): Examples include, narrowing of the aorta called coarctation of aorta and narrowing of pulmonary artery called pulmonary artery stenosis

What is the cause of Stroke?

When a child has CHD, there are several ways in which it might lead to a stroke. The most common cause is that a clot (thrombus) forms in the heart, travels to a vessel in the brain and blocks blood flow causing loss of oxygen supply and death of certain brain tissue (thromboembolism). The risk of stroke is usually more around the time of heart surgery. Other possible causes of stroke include:

- Paradoxical embolism: A blood clot that forms in veins travels to the brain through a hole in the heart.

- Hyperviscosity: Blood becomes too thick due to an increased number of red blood cells (polycythemia) or other compensatory mechanisms. This thicker blood can form clots, leading to a stroke.

- Infective endocarditis: Infection of the heart’s inner lining can cause clumps of bacteria or blood clots (septic emboli) to break off and travel to the brain. Children with CHD are at increased risk of infective endocarditis.

- Dilation of heart chambers: The heart may become enlarged, causing blood to pool inside, leading to blood clot formation.

- Arrhythmias: Abnormal heart rhythms can result in blood clots, which may cause a stroke.

What are the symptoms of stroke?

What are the symptoms of stroke?

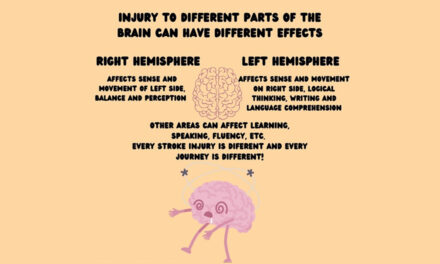

Stroke symptoms can differ between infants/young children, and older children. Identifying these symptoms is essential in seeking prompt medical care.

Stroke symptoms in infants and young children can include focal weakness (weakness in a specific part of the body) but are more commonly present as seizures, altered sensorium (changes in mental function such as confusion). Older children experiencing stroke often exhibit weakness on one side of the body (hemiparesis) or other focal (localized) neurological signs such as difficulty with speech (aphasia), vision problems, issues with balance and coordination (cerebellar signs), sudden changes in behavior, and confusion. They may also present as seizures and headaches.

Furthermore, strokes related to cardiac disease are more likely to occur while the child is hospitalized with the highest risk of experiencing arterial stroke during heart surgeries, emphasizing the importance of close monitoring in these cases.

Management:

Prompt action is crucial when dealing with a suspected stroke while the child is at home. By following these essential steps, we can ensure a swift response and potentially minimize long-term complications:

- Seek immediate assistance: Contact emergency services, call 911 right away if you suspect a stroke, or have someone nearby make the call while you attend to the individual. It is also important as a parent/caregiver to know where the nearest children’s hospital is located.

- Record the onset time: Knowing when symptoms first appeared is vital, as it can greatly impact treatment options and outcomes.

- Ensure the individual’s comfort: Place them in a safe position, ideally on their side with their head slightly raised. Loosen any tight clothing and provide reassurance while awaiting emergency services.

Once at the hospital, medical professionals will conduct various tests to assess the situation and identify the underlying cause of the stroke. These tests may include:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Angiography: These imaging techniques provide detailed pictures of the brain and blood vessels supplying it, helping doctors to identify any abnormalities or blockages.

- Blood tests: Laboratory analysis of blood samples can reveal potential risk factors and aid in determining the cause of the stroke

- Cardiac examination: Evaluating the heart’s function and structure can help detect any cardiac issues contributing to the stroke.

Treatment:

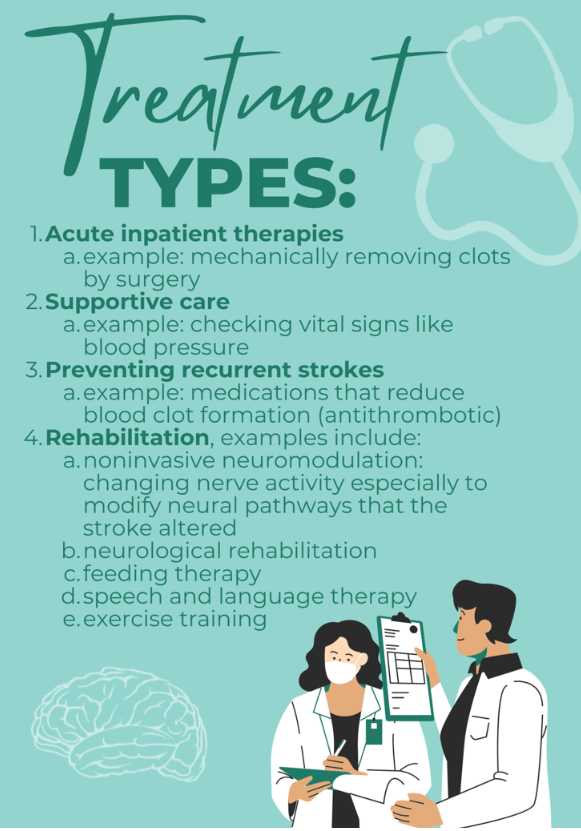

Stroke treatment generally focuses on four key areas:

-

- Acute inpatient therapies: These treatments aim to open blocked blood vessels, restoring blood flow to undamaged brain regions through procedures like thrombolysis (dissolving clots with drugs) or thrombectomy (mechanically removing clots by surgical devices). There’s an ongoing debate about using fast-acting therapies for arterial stroke (when an artery to the brain is blocked) in children because there’s not enough information from clinical trials for young patients. The child’s treatment will therefore be personalized and determined through collaborative decision-making involving neurologists and other specialized departments in the field.

- Supportive care: Ensuring stable vital signs and providing necessary care to minimize potential complications. Post-stroke care for children involves close monitoring in the ICU and maintaining stable vital signs, including normal to slightly high blood pressure, temperature, and blood sugar levels. Proper positioning, typically lying flat, helps maximize blood flow to the brain and prevents further injury.

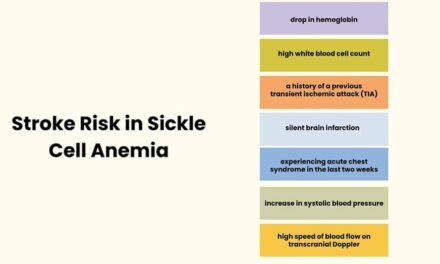

- Prevention in Children: Preventing the first arterial stroke in children is challenging due to various underlying causes. The primary focus of treatment, like in adults, is preventing recurrent strokes. While newborns usually have a low risk of recurrent arterial stroke (except in the case of complex CHD), older children may have a higher risk. Antithrombotic medications (medications that reduce blood clot formation) such as aspirin and warfarin are commonly used for stroke prevention in both children and adults, with appropriate precautions. These medications appear safe for initial arterial stroke treatment, except if patients have certain conditions like severe bleeding disorders.

-

- Antithrombotic medications (blood thinners) for stroke prevention in CHD:

Doctors use two types of blood thinners for stroke prevention: anticoagulants, like heparin, and antiplatelets, like aspirin. Anticoagulants are stronger blood thinners that doctors think work better for blood clots in the heart, but they are more likely to cause bleeding than antiplatelets. For suspected stroke due to thrombus (blood clot) in the heart, doctors often start with anticoagulation and switch to aspirin if subsequently no clot in the heart is found. For confirmed cases of a clot in the heart, doctors often treat with anticoagulation through an intravenous (IV) line, followed by anticoagulants that can be taken at home (like low molecular weight heparin or warfarin) for 3-6 months, with aspirin as an alternative. Doctors will weigh the risks and benefits of anticoagulants in every individual child; aspirin might be the appropriate first step in children with high risk of bleeding. Consult a pediatric cardiologist and hematologist for risk assessment and long-term treatment plans.

- Antithrombotic medications (blood thinners) for stroke prevention in CHD:

-

- Rehabilitation: Rehabilitation therapies significantly support recovery in children with stroke. New approaches like constraint-induced movement therapy encourage using the affected limb more while constraining the unaffected limb, improving motor skills. Noninvasive neuromodulation (changing nerve activity especially to modify neural pathways that the stroke altered), alongside physical or occupational therapy, stimulates brain areas to improve treatment outcomes. Other approaches include:

- Neurological Rehabilitation: Focusing on motor, speech, cognitive, and feeding abilities to enhance function and quality of life.

- Feeding Therapy: Addressing feeding difficulties, supporting growth and development.

- Speech and Language Therapy: Targeting communication skills and language comprehension.

- Exercise Training: Improving physical fitness and overall well-being

- Multidisciplinary Team Approach: Collaboration among diverse specialists to address various needs.

These tailored techniques aim to enhance the functional abilities, independence, and overall well-being of children with stroke occurring in the setting of a CHD.

References

- Ferriero DM, Fullerton HJ, Bernard TJ, Billinghurst L, Daniels SR, DeBaun MR, et al. Management of stroke in neonates and children: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American stroke association. Stroke [Internet]. 2019;50(3). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/str.0000000000000183

- Asakai H, Cardamone M, Hutchinson D, Stojanovski B, Galati JC, Cheung MMH, et al. Arterial ischemic stroke in children with cardiac disease. Neurology [Internet]. 2015;85(23):2053–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000002036

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ischemic-stroke-in-children-management-and-prognosis

- Sinclair AJ, Fox CK, Ichord RN, Almond CS, Bernard TJ, Beslow LA, Chan AK, Cheung M, deVeber G, Dowling MM, Friedman N, Giglia TM, Guilliams KP, Humpl T, Licht DJ, Mackay MT, Jordan LC. Stroke in children with cardiac disease: report from the International Pediatric Stroke Study Group Symposium.Pediatr Neurol. 2015; 52:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.09.016

About the Author

Rushel Chowhan, MBBS

General Practitioner

Manipal College of Medical Sciences, Nepal

Dr. Chowhan is a dedicated medical professional from Nepal with a passion for neurology. A graduate of Manipal College of Medical Sciences, he aspires to specialize in the field of neurology and make significant contributions to healthcare.

Driven by his commitment to accessible healthcare and community outreach, Dr. Chowhan has volunteered at free clinics in Nepal. He is currently working as a medical officer aiming to combine his medical knowledge with practical and interpersonal skills to navigate the evolving healthcare landscape.

In addition to his clinical work, Dr. Chowhan enjoys sharing his knowledge through writing, and content creation. He has contributed to healthcare policy in Nepal, playing a crucial role in addressing childhood malnutrition. An accomplished author, his works range from newspaper articles and scientific papers.

When he’s not occupied in the world of medicine, Dr. Chowhan enjoys spending time with friends and family, indulging in his love for music by playing the guitar, and staying active on the soccer field.

Gayatra Mainali, MD

Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Neurology

Penn State Health Children’s Hospital and Penn State College of Medicine

Gayatra Mainali MD is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Neurology and Penn State Children’s hospital and Penn State College of Medicine. She completed her pediatric residency from Brookdale University Medical Center in Brooklyn, NY in 2007 and Child Neurology residency at Cleveland Clinic, OH in 2013. She joined Penn State since 2013 and has an interest in Epilepsy and Stroke. She enjoys teaching and learning from medical students and residents. She has received several teaching awards and published in peer reviewed journals.

Medical Editors: Manish Parakh, MD

Junior Editor: Christine Zhang and Karen Glenn