Introduction

Pediatric stroke causes motor impairments in up to 80% of children with stroke. A motor impairment means that part of the body doesn’t work, partially or at all. This is often caused by brain injury, such as strokes.

Why would an injury to the brain cause problems with a body part? The brain sends signals – like instructions – to the muscles, telling them how to move. If there is damage to a certain part of the brain, like an area that controls movement, then those signals cannot get through properly. As a result, the muscles in one part of the body do not get instructions to move properly.

Common Motor Impairments After Pediatric Stroke

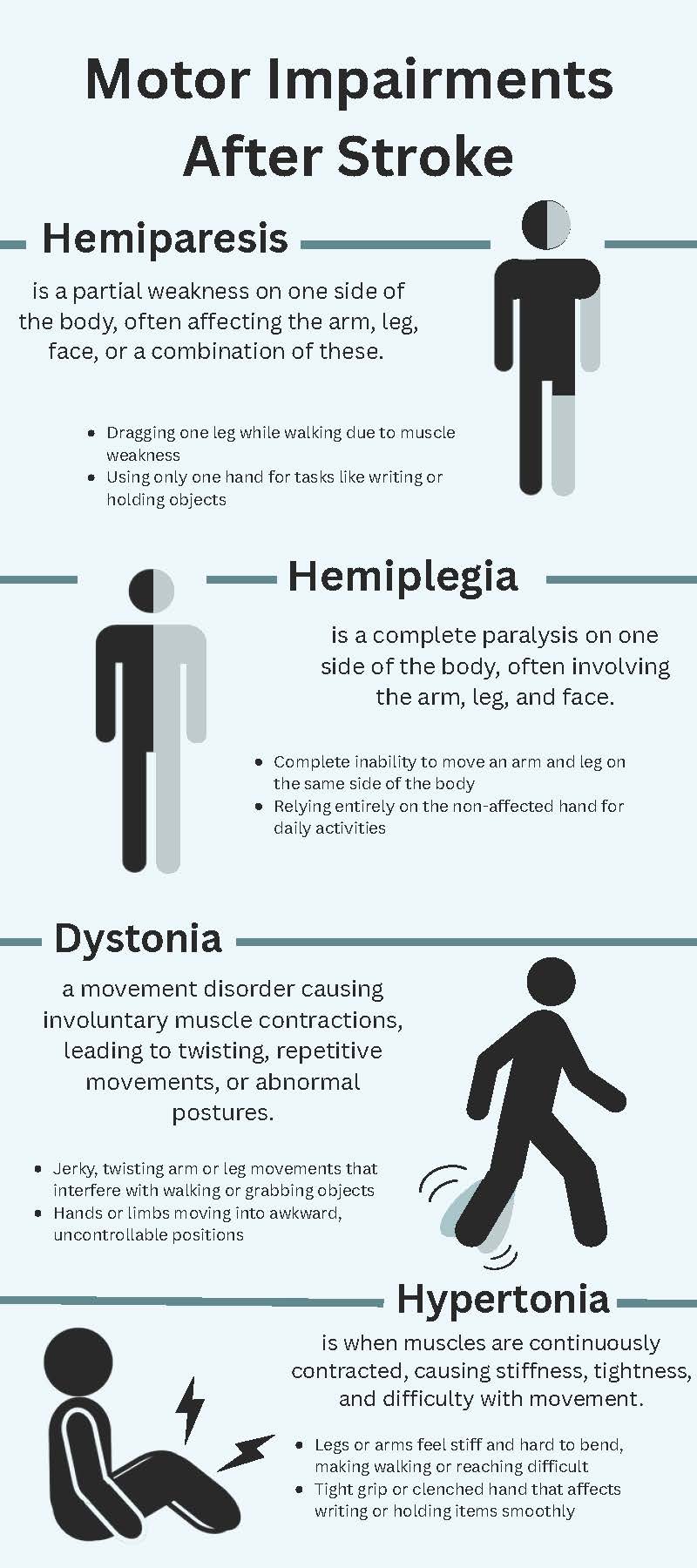

Common motor impairments after pediatric stroke include hemiparesis, hemiplegia, dystonia, and hypertonia. The severity of these problems can be different for each child. Many children can gain or regain the ability to move on their own. Ongoing research has found that children with motor impairments feel that the most important factors affecting their quality of life are movement and balance issues. Even mild motor problems may limit a child’s ability to participate in activities and affect the child socially and emotionally.

Hemiparesis

Hemiparesis means weakness on one side of the body. Paresis can also occur in smaller areas, like one side of the face, one hand, or one leg. It can come with sensory loss too, which means that the person cannot feel things in the same way that they can feel in other parts of their body. Over time, the muscles on the weaker side can become stiff, overworked, or strained, causing pain. Pain can also happen because of improper posture.

Imagine a young girl with right-sided hemiparesis. When she walks, her right leg might have trouble lifting off the ground because it is weaker. She may have to swing it to the side or drag it along. Over time, she develops pain in her foot because it stays in an uncomfortable position. Her right arm might seem limp and may not swing like the left arm does. If she tries to pick up an object, her right hand might not grip or hold it properly, so she might use her left hand instead. When trying to write, her right hand might have difficulty controlling movements or might be too weak to hold the pencil correctly.

Hemiplegia

Hemiplegia is a more severe form of hemiparesis; it refers to severe or complete weakness, also called paralysis. Like hemiparesis, it can impact one entire side of the body or a smaller area like a hand. It can also be associated with sensory loss. It can also cause pain from poor posture or because the other side of the body tries to compensate.

Imagine a young boy with right-sided hemiplegia. His right arm and leg would be paralyzed or very stiff. He would have trouble moving his right leg when walking, so he might drag it or not be able to step forward at all. His right arm would stay by his side, not moving. When he tries to pick up an object, he would not be able to use his right hand and would rely on his left hand instead. In fact, many children switch their handedness if they have hemiplegia or hemiparesis, and they work hard to learn to write with their non-dominant hand.

Dystonia

Dystonia refers to an uncontrollable muscle contraction that looks like jerky movements, spasms, and twisted postures. Dystonia can impact various parts of the body like the neck, hands, or legs. The movements might happen constantly or in bursts. They can be uncomfortable, tiring, and painful because the constant contractions can put stress on joints and tissues.

Imagine a girl with dystonia after her stroke. When she is walking, her body might twist or her feet might drag, making her steps uneven or jerky. Her arms could twist into awkward positions, and she might not be able to straighten them easily. If she is trying to pick up an object, her hand might grip tightly or move in a strange way, making it hard for her to grab it and hold onto it. The movements could be painful for her, like a cramp or “Charley horse,” because her muscles are exhausted or her nerves are compressed from the bursts of contractions.

Hypertonia

Hypertonia refers to the brain sending excess signals telling muscles to contract, causing rigidity and spasticity. This happens because the muscles are contracting too much. Spasticity and rigidity make it hard to move smoothly and to stretch muscles. It can also be painful and tiring. It can even make muscles not directly affected by spasticity stiff, because they are working even harder to make up for the weaker ones.

Imagine a boy who has hypertonia due to a stroke. When he tries to walk, his legs might be stiff, so they do not bend as they should for walking. He might have trouble lifting his legs, so he might drag his feet. His arms could also be stiff. If he tries to pick up an object or write, his grip might be too tight, so his movements would not be smooth or coordinated. He might be in pain or tired often.

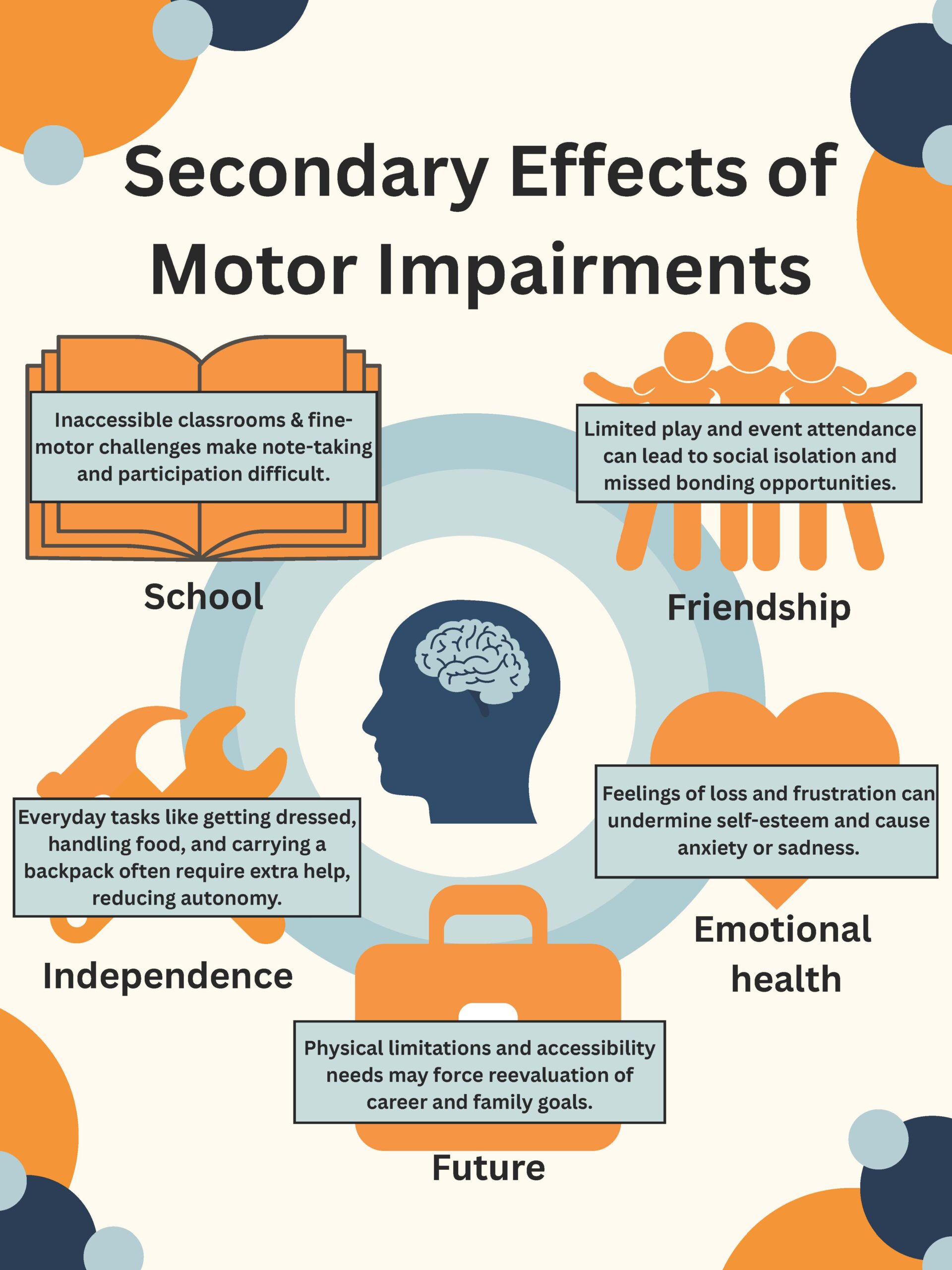

The Ripple Effect: Secondary Impacts of Motor Impairments

Stroke survivors report that their motor impairments do not only affect motor functions – they also have ripple effects across many other areas in life like school, social functioning, emotional well-being, independence, and future planning.

School

At school, inaccessible spaces make it difficult for a child with motor impairments to get around safely and smoothly. For instance, the child might need someone’s help to walk up the stairs. If they have difficulties with fine motor skills (small, controlled movements), they might write slowly, not legibly, or not at all. They may require someone to take notes for them or specialized equipment such as a laptop to type their notes.

Social functioning

Many children with stroke participate less in social events and outings because of their motor impairments. For example, a toddler who cannot run cannot play tag with their friends. Motor impairments often prevent children from playing sports and joining teams, which is an important way to make friends. Children with motor impairments also can’t join their friends when the plan involves locations that are not accessible, or when the physical activity is too difficult (e.g., hiking, walking all day). They sometimes miss opportunities to see their friends because of physical therapy appointments or the need to rest, since motor impairments can cause pain and tiredness.

Emotional well-being

Motor impairments can cause frustration, anger, and sadness. For those who experienced a stroke when they were old enough, they can remember what it was like before their stroke and before their motor impairment. Many pediatric stroke survivors feel sad by the hobbies and activities they have had to give up because of motor impairments; maybe they can no longer play their musical instrument, they can no longer compete in sports, or they can no longer paint in the same way. Giving up these activities can also hurt a person’s sense of identity and self-esteem.

Imagine a girl who loved soccer– she was on the school team, her teammates were her best friends, and she was planning to play soccer her whole life, maybe even professionally. After her stroke, losing all of this because she cannot play soccer anymore can be upsetting and hard to accept.

Independence

Motor impairments can make simple day-to-day tasks difficult. Simple tasks that require the use of both hands might become hard or impossible, such as opening a jar, tying shoelaces, or fastening buttons on clothes. Children who have had stroke might be more likely to hurt themselves or to damage things. Imagine someone with hemiparesis balancing a set of plates with one arm, or someone with dystonia carrying a water pitcher and experiencing sudden uncontrollable jerks. Of course, complex tasks such as making breakfast, showering, or cleaning a room become difficult with motor impairments too. When many day-to-day activities suddenly become difficult or impossible, there is a significant loss of independence for stroke survivors, who have no choice but to rely on others.

Future planning

Recent research shows that many pediatric stroke survivors re-think their plans for their future. For example, motor impairments limit career possibilities. Jobs that require strength and speed (e.g., police officer, firefighter), fine motor skills (e.g., nurse, surgeon, artist), or hand-eye coordination (e.g., athlete) may not be options anymore. Some stroke survivors have also discussed the implications for their own future families. Motor impairments can make it difficult to hold a baby safely or to care for a young child. Some stroke survivors think deeply about whether they feel comfortable raising children and whether their family plans need to change.

Conclusion

Motor impairments like hemiparesis, hemiplegia, dystonia, and hypertonia, are common after pediatric stroke. To really understand what life is like for children who survive a stroke, it’s important to learn about how these motor impairments affect more than movement and physical activity. These motor impairments can create a ripple effect that spreads far — like a stone dropped in water — reaching into many areas of daily life, from school and friendships to independence and future goals.

About the Author

Dr. Claire Champigny, Ph.D., C.Psych

Dr. Claire Champigny is a postdoctoral fellow in clinical pediatric neuropsychology at the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Canada). She conducts neuropsychological assessment for children with a range of medical histories across clinics (e.g., Neurology, Neurosurgery, Oncology), and also works as a therapist providing support for parents of children with behavioural challenges and complex medical needs. Dr. Champigny’s research interests primarily revolve around neurocognitive and mental health outcomes following pediatric stroke.

Dr. Champigny is happy to answer questions and receive feedback about her article. Please contact her via email at claire.champigny@sickkids.ca.

Graphics: Sanjana Sivakumar

Medical Editors:Kevin O’Connor

Junior Editor: Sanjana Sivakumar